Inductors are indispensable components in RF and microwave circuits, playing crucial roles in filtering, impedance matching, and signal tuning. However, their behavior at high frequencies is far from ideal due to inherent parasitic elements that limit their performance. One key parameter that defines the usable frequency range of an inductor is its self-resonant frequency (SRF) – the point where the inductor’s parasitic capacitance resonates with its inductance, causing it to lose its inductive properties. In this blog, we will explore the concept of SRF, analyze how parasitic elements influence it, and compare two spiral inductors with different geometries to understand the trade-offs involved in high-frequency inductor design.

Parasitic Elements in Real-World Inductors

No inductor is purely inductive. All practical inductors exhibit three parasitic elements that degrade performance at high frequencies:

-

Equivalent Series Resistance (ESR)

-

Arises from the resistive losses in the conductor material (e.g., copper traces) and substrate coupling.

-

Causes power dissipation, reducing Q-factor and efficiency.

-

-

Equivalent Parallel Capacitance (EPC)

-

Generated by:

-

Inter-winding capacitance between adjacent spiral turns.

-

Substrate capacitance between the inductor and ground plane.

-

Fringing fields at the edges of the metal traces.

-

-

Forms a resonant tank with the inductor’s inductance (L), creating the self-resonant frequency (SRF).

-

-

Distributed Parasitic Inductance

-

Even non-inductive components (e.g., traces, vias) exhibit unintended inductance due to current flow paths.

-

Affects high-frequency impedance and signal integrity.

-

The Self-Resonant Frequency (SRF) Phenomenon

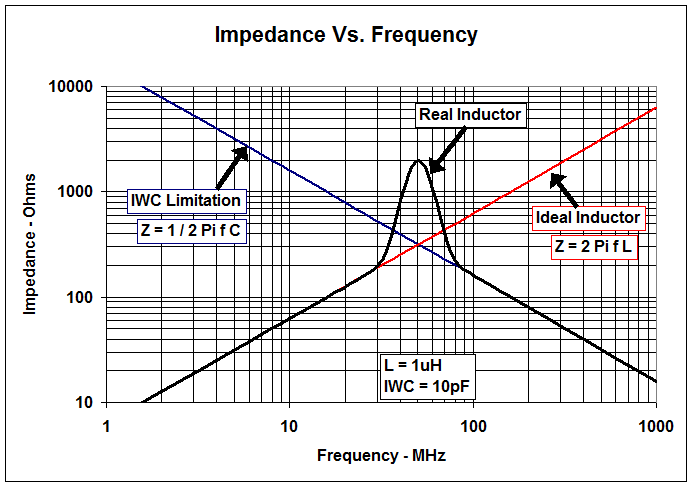

The SRF occurs when the inductor’s parasitic capacitance (Cp) resonates with its inductance (L):

SRF=12πL⋅Cp

-

Below SRF: The inductor behaves as intended, with impedance increasing linearly (Z=jωL).

-

At SRF: The impedance peaks (Z→∞), creating an open circuit due to parallel resonance.

-

Above SRF: The parasitic capacitance dominates, turning the inductor capacitive (Z=1/jωCp).

Impact of Parasitics in RF Circuits

-

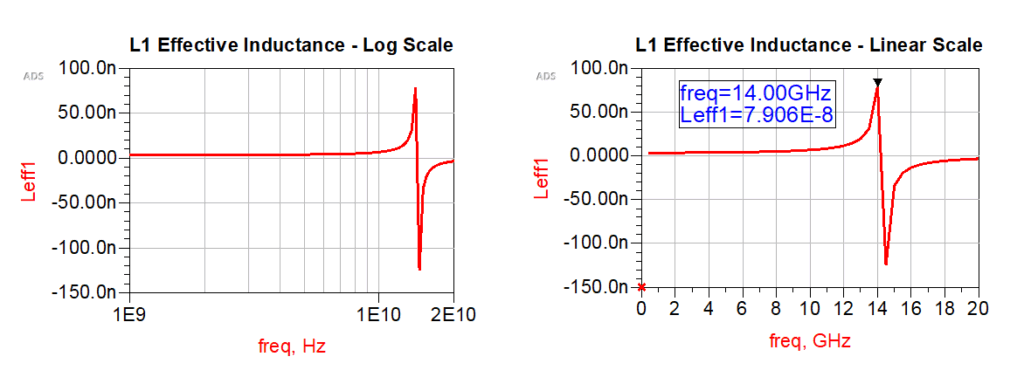

Signal Paths: Operate inductors below SRF to avoid nonlinear behavior. For example, a 14 GHz SRF inductor should be used below ~10 GHz.

-

Bias Chokes: Intentionally operate near SRF to maximize impedance for noise rejection.

-

Layout Sensitivity: Substrate thickness and dielectric constant (ϵr) directly influence Cp. Thinner substrates (e.g., GaAs) increase Cp, lowering SRF compared to thicker substrates like alumina

Experimental Setup

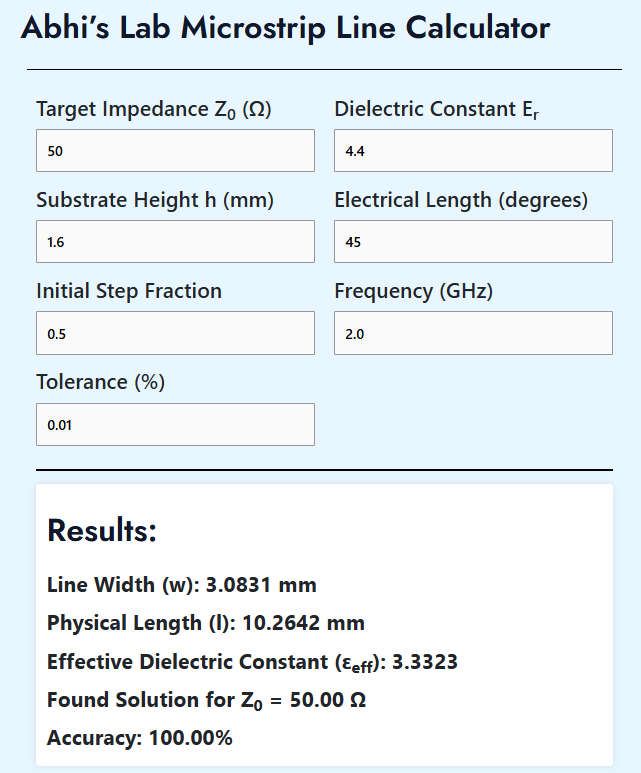

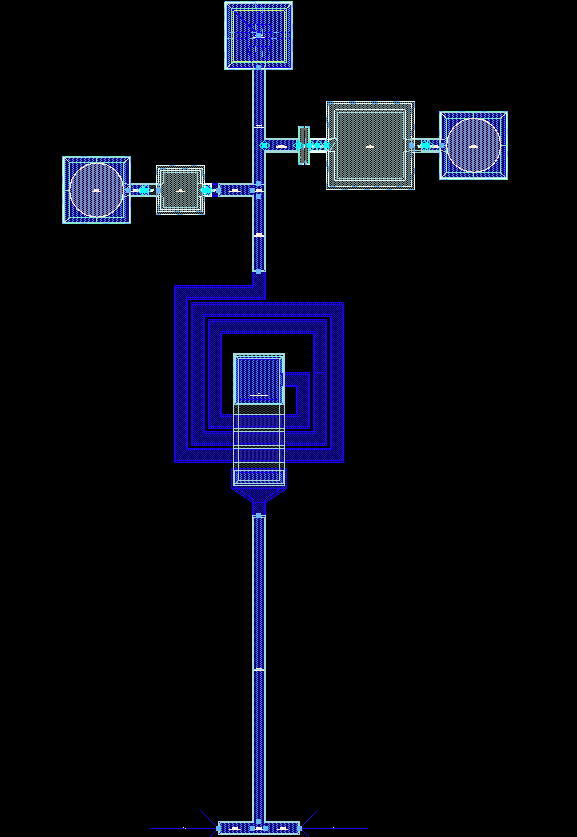

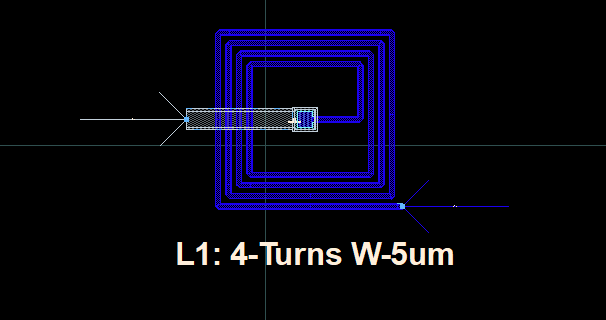

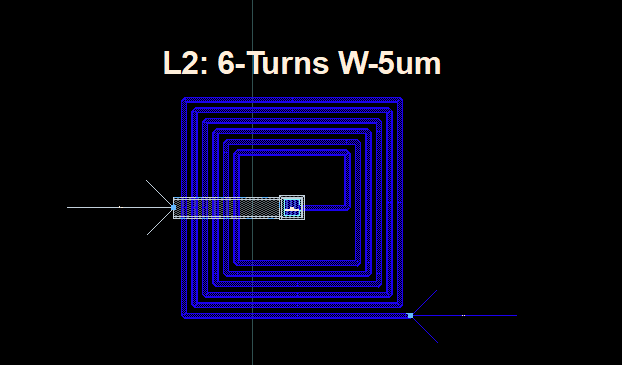

To investigate the self-resonant frequency (SRF) behavior, we designed and simulated two spiral inductors, each terminated with 50 Ω ports at both ends. Both inductors were fabricated with a line width (w) of 5 μm, but differed in the number of turns: one with 4 turns (L1) and the other with 6 turns (L2).

The simulations were performed using the Momentum Microwave EM simulator, sweeping from 0 to 20 GHz. To ensure high accuracy, the mesh was set to 50 cells per wavelength, which is a common practice for compact inductor structures and provides reliable results for fine geometries. This setup accurately captures the electromagnetic effects and parasitic coupling present in real-world inductors.

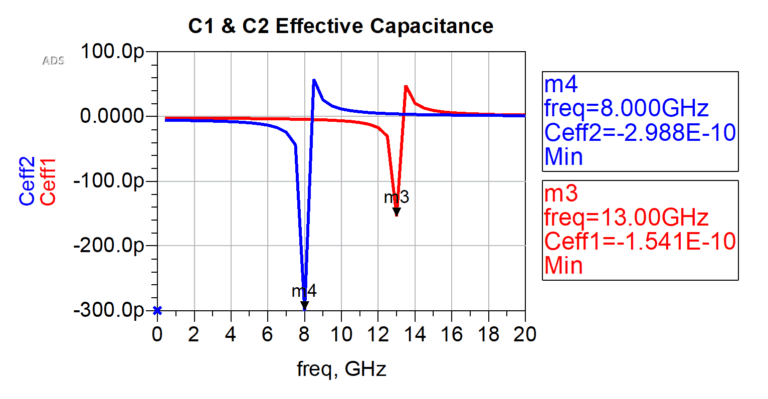

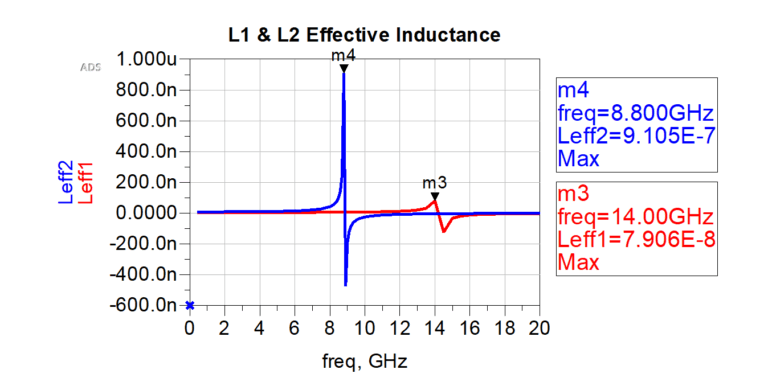

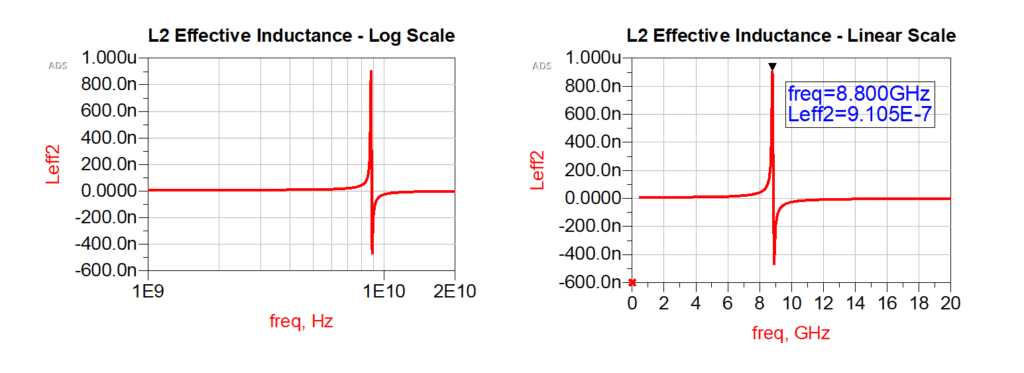

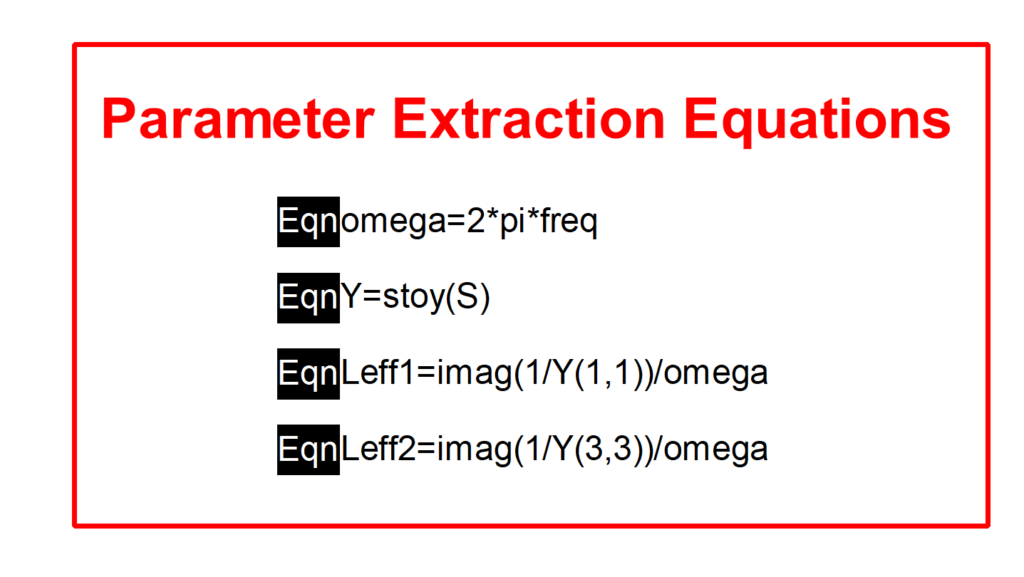

After simulation, we extracted the effective inductance (Leff) for both inductors using the parameter extraction equations (see image below for details on the equations used). The extracted Leff was then plotted against frequency to visualize the frequency-dependent behavior of each inductor.

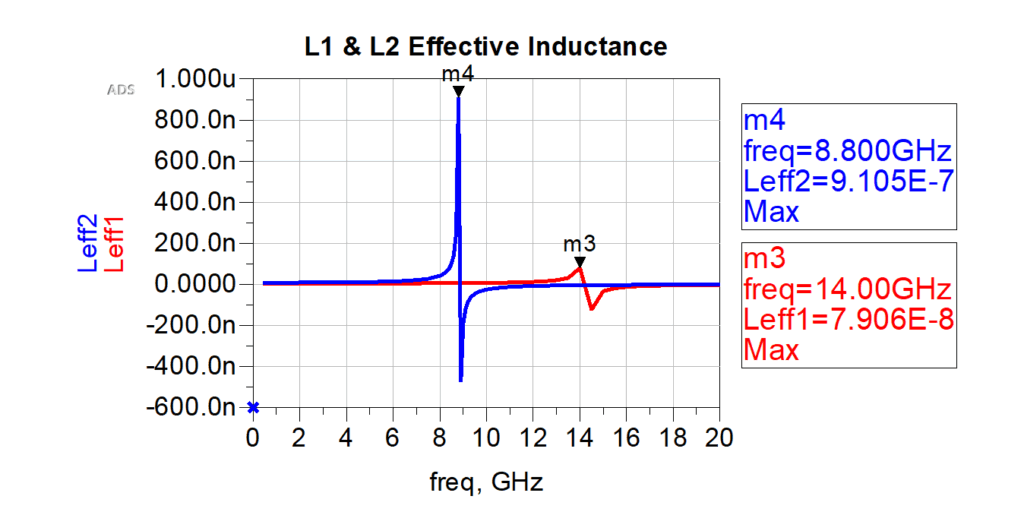

Next, we compared both inductors by plotting Leff1 (Red, 4-turn inductor) and Leff2 (Blue, 6-turn inductor) on a single graph. This comparison clearly shows that the 4-turn inductor (L1) exhibits a higher SRF at 14 GHz, while the 6-turn inductor (L2) has a lower SRF at 8.8 GHz. Additionally, the maximum effective inductance observed for L1 is 79 nH, whereas L2 reaches a much higher value of 910 nH at resonance, resulting in a more pronounced spike in the plot.

Applications and Design Considerations

The choice between these two inductor designs depends on the intended application:

For RF Signal Path Applications:

-

Operation should be well below SRF in the linear region

-

L1 (4-turn) can be operated below 10 GHz.

-

L2 (6-turn) would be better for frequencies below 7 GHz

For Bias Path/Choke Applications:

-

Operation near (just below) SRF provides maximum impedance for signal blocking

-

L1 would be effective as a choke at frequencies around 11-14 GHz

-

L2 would be effective as a choke at frequencies around 7-8.8 GHz

It is suggested that for inductor to be used at RF path, the operating band should be in linear region, which can be found from the Leff Plot.

Practical Design Implications

When designing spiral inductors for specific applications, consider these key factors:

-

Number of turns: Increasing turns raises inductance but lowers SRF

-

Line width: Wider lines reduce resistance but may increase parasitic capacitance

-

Spacing between turns: Larger spacing reduces inter-winding capacitance but may lower inductance density

-

Overall size: Smaller inductors typically have higher SRF but lower inductance

For optimal performance in your specific application, simulate different inductor geometries and evaluate the trade-offs between inductance value, SRF, and quality factor.

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of these two spiral inductors demonstrates the fundamental trade-off in inductor design between inductance value and self-resonant frequency. Understanding these relationships is crucial for RF circuit designers to select or design inductors that will perform optimally in their specific frequency range and application.

Whether you need a higher inductance value for matching networks or a higher SRF for high-frequency applications, this study provides insights into how geometric parameters affect inductor performance and how to choose the right design for your specific requirements.